By Richie Venton, SSP Workplace Organiser

First published HERE

Read more from Richie at richieventon.blogspot.com

On a hot 30 July 1971, the shop stewards in Clydebank’s John Brown shipyard took control of the yard gates as the historic UCS work-in began.

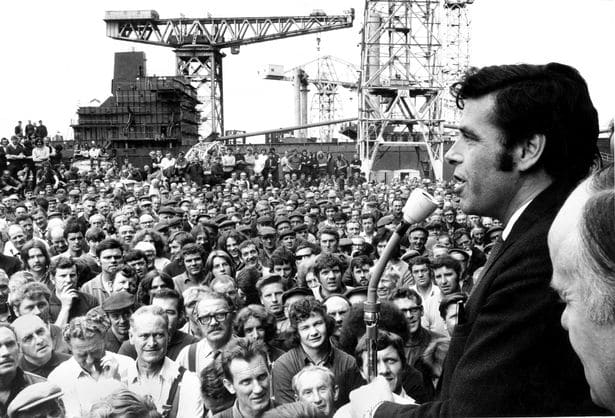

Jimmy Reid declared to the mass meeting inside: “There will be no hooliganism, there will be no vandalism, there will be no bevvying, because the world is watching us.”

Thus began one of the most momentous showdowns by working people since the 1926 general strike.

UCS had been formed in 1968, comprising the yards in Govan, Linthouse, Scotstoun and Clydebank. The naked greed of shipbuilding dynasties had meant a refusal to invest and modernise, causing Britain’s world share of shipbuilding to plummet from 80% during WWI to 5% in 1970. Mergers and mass redundancies in the 1960s ran alongside increased productivity by the workers. The 1964-70 Labour government refused to nationalise the industry, instead merging the UCS yards, with a 17% government share.

In 1969, the notorious Tory, Nicholas Ridley, held a one-hour meeting on the Clyde with his pal Sir Eric Yarrow, owner of Yarrow’s shipyard and Scottish Tory Party treasurer. ‘Old Nick’ subsequently drafted his Ridley Memo: “We could appoint a government butcher to cut up UCS, hive off Yarrow’s and sell (cheaply) the remainder of UCS to private industry.” (December 1969)

Tory Spirit of Butchery

Ted Heath’s 1970-74 Tory government proceeded in this spirit of butchery, consciously confronting workers and their rights, deliberately decimating industry and speeding up monopoly ownership of what remained. Tory Minister of Trade and Industry, John Davies, spelled it out with his infamous ‘lame ducks’ speech, declaring an end to state subsidies to industries in crisis, especially targeting Rolls Royce and UCS.

In June 1971 the Tory government triggered the liquidation of UCS by refusing management’s modest demand for £6million to sustain it. They instead conceded £3million to keep UCS afloat until August, whilst conducting a bogus review by ‘The Four Wise Men’, comprising mostly merchant bankers. Their subsequent Report smeared shipyard workers and recommended the slaughter of 6,500 of the 8,500 jobs, with closure of Clydebank and Scotstoun, only keeping Govan and Linthouse on the basis of decimated conditions and halving of the workforce.

The baying mob of Tory MPs who cheered these announcements badly underestimated the response of the UCS workers and hundreds of thousands who came to their side in a 14-month battle that engulfed society in Scotland and beyond.

Work-In, not Walk-Out

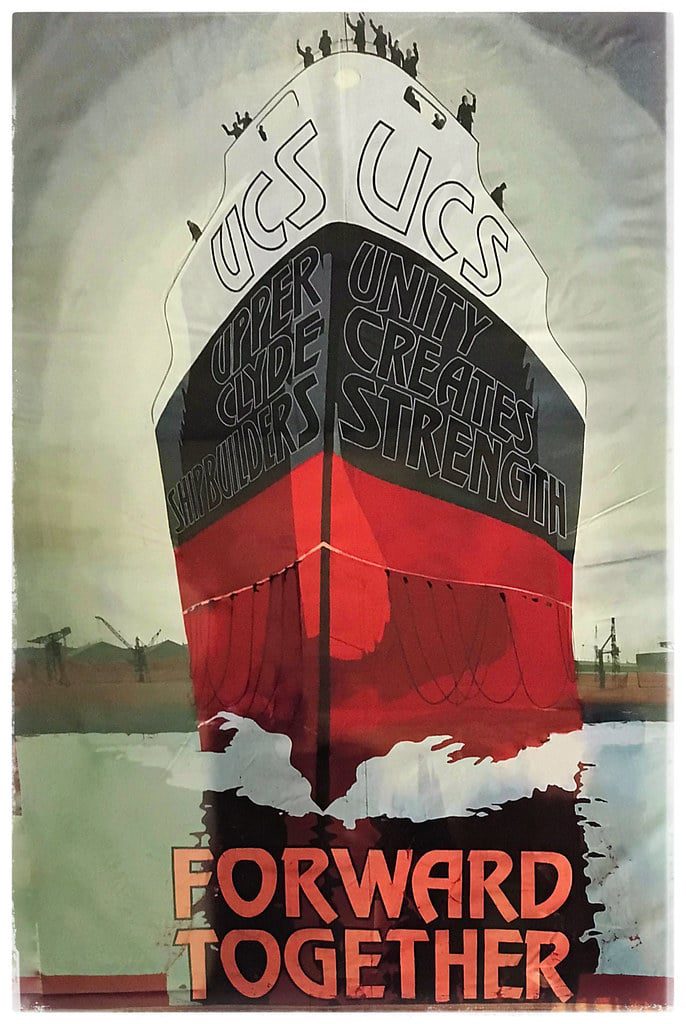

In June 1971, the Union shop stewards from the four yards decided that instead of walking out to the Labour Exchanges (JobCentres) or being declared redundant they would occupy the yards and continue production of ships; a work-in. Their opening demands were “Not a man down the road – the right to work – not a yard will close.”

They sent delegations to the government, only to be ‘slung a deafie’. The fight was on. They called a West of Scotland conference of shop stewards, 800 strong, which announced a general strike and demonstration on 23 June. About 150,000 took solidarity strike action and 50,000 marched through Glasgow. Placards carried slogans like ‘Launch UCS – Sink Heath’ and ‘Nationalise not Paralyse – we shall not be moved’. The STUC at first called for nationalisation of the yards.

When on 29 July the government tried to ride this storm and announced 6,500 job losses – with at least another 15-30,000 associated jobs to go – the working class of Scotland and beyond were inspired by the act of mass, militant defiance by the UCS workers.

A conference of 1,200 shop stewards from Scotland and the North of England agreed financial support to sustain the work-in, and called a mass half-day strike and demo on 18 August. About 200,000 workers marched out of Scottish workplaces and joined the demo of 80-100,000 in George Square, the biggest since at least the days of Red Clydeside; some reckoned the largest since the Chartist movement of the 1840s. The themes of the right to work and the power of the working class in solidarity were combined with calls to kick out the Tory government. Industrial and political demands fused.

Unprecedented Solidarity

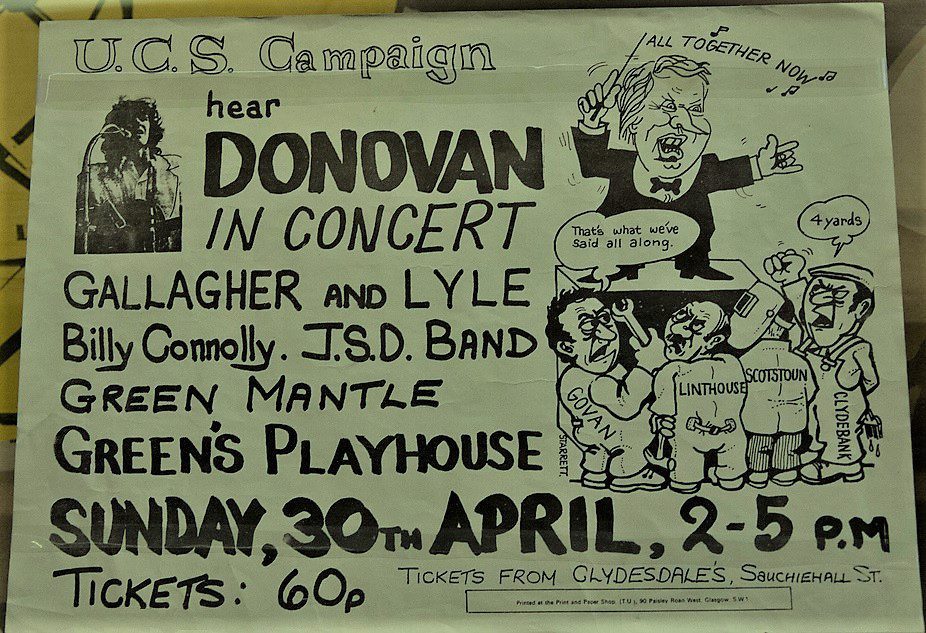

The UCS workers’ courageous defiance evoked unprecedented solidarity. Workplace collections and weekly levies came from across Scotland, Britain and as far afield as New Zealand. Combined with the 50p a week levy on the UCS workers themselves, this financial solidarity sustained the wages of the work-in and the campaigning costs. School students held jumble sales. Pensioners donated. A cleaner in Yorkshire sent a week’s wages every month.

Workers’ heads were raised because a group of trade unionists defied every law, every conservative norm, and waged the battle for the right to work from the stronghold of staying inside their own workplace. The occupied yards were their fortresses, with buses between the yards for mass meetings; a Coordinating Committee and several sub-committees, including ones for finance and publicity, and speaking tours of workplaces that trained hordes of orators.

Even the middle layers of society were drawn to this mass workers’ movement, with virtually every local shopkeeper publicising the UCS struggle, and donations famously from John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Such was the ferment that Sir David MacNee, Glasgow’s chief constable, phoned a Cabinet meeting to warn the government that the police couldn’t guarantee order in the city if the yards were closed. The government postponed the closure announcement by two weeks to allow them to bring troops back from Northern Ireland!

Monumental Government U-turn

In the subsequent months the government tried manoeuvres to divide and conquer, especially by declaring a new Govan Shipbuilding Ltd, initially only embracing Govan and Linthouse.

Eventually, by February 1972, they were forced into a monumental retreat. In contrast to their refusal to cough up £6million the previous June, the same John Davies told the House of Commons on 28 February 1972 that the Tory government would hand over £30million to Govan Shipbuilders Ltd, which would now also include the Scotstoun yard, and look favourably on subsidies to the impending buyer of Clydebank – the USA oil-rig giant, Marathon Manufacturing.

Months of negotiations did involve very substantial concessions by the unions, with loss of jobs and severe sacrifices of conditions, but the four yards remained and about 6,500 of the 8,500 jobs were saved. This was a massive victory compared to the wholesale butchery that any meek-and-mild response from their unions would have guaranteed.

Perhaps the biggest significance of the UCS work-in was on the wider working class and political developments. It was part of a rising tide of industrial action engulfing the Heath government, but added impetus and confidence to it. A major factor in the February 1972 government U-turn on UCS was their bloody-nosed defeat just days prior by the miners, in their first national strike since 1926, which included the NUM’s mass picket attracting 15,000 workers, which shut down the Saltley coke depot, near Birmingham.

Mass Defiance Can Win

The limitations of a work-in with continued production of ships – as compared with an occupation and strike – could be the subject of a whole separate article. This issue came to a head in January 1972, when the UCS Coordinating Committee reversed their earlier stance and agreed to launch one of the newly built ships (at the Govan yard) as ‘an act of good faith’, rather than a full-blown showdown with the government which had been their policy up until then. How many more jobs could have been saved and conditions protected if they had stuck to their original policy, combined with the battle for nationalisation of the yards, will never be known for certain.

What was known at the time – by tens of thousands of working people – is that the mass defiance of occupying the yards built unprecedented workers’ unity and solidarity and forced a humiliating U-turn on a Tory government just as vicious in its desire to butcher jobs and conditions as the current Boris Johnson cabal.

Over and beyond that, UCS demonstrated workers’ control in practice, and the managerial skills of working-class people – a glimpse of a socialist future where capitalist owners and their enforcers, in the form of senior management, would be redundant.

Lessons 50 Years On

50 years on, as we exit the period of COVID-19 lockdowns, workers are confronted by closures, mass redundancies and systematic attacks on workplace rights, including the new capitalist pandemic of Fire and Rehire. Amongst the many lessons from UCS that need to be applied is that pleading with the bosses and their governments guarantees defeat for workers and their communities, whereas methods of mass collective struggle that brush aside the whole machinery of anti-trade union legislation can win victories.

The brutal determination by Pladis multinational to close the McVitie’s factory is a classic current example of where the methods of the UCS workforce would be required to reverse the butchery of jobs and livelihoods.

As part of the crazed drive for short-term profiteering – through the conscious destruction of industry and the financialization of the economy – in the decades since UCS, the shipyards on the Clyde are barely a shadow of their former selves, and heavily dependent on production orders for war, rather than socially useful production.

Socialism or Barbarism

50 years on, the climate catastrophe and the capitalist economic crisis highlighted and exacerbated by COVID-19, both scream out for a green re-industrialisation of Scotland; a Socialist Green Recovery plan, embracing the skills and equipment of what remains of the shipyards. For example, to build the desperately needed fleet of ferries, and marine engineering equipment for the production of clean, green, affordable energy.

Everyone talks these days about ‘recovery’. But perhaps the most central recovery required is the working-class solidarity and fighting spirit epitomised by the UCS workers and their hundreds of thousands of allies 50 years ago. Without such a revival of collective action by organised workers and the solidarity which that would undoubtedly evoke, the capitalists and their hired governments will continue to wreak havoc and destruction on jobs, living standards, democratic rights and the very planet we live on.

Socialism or barbarism is not empty rhetoric, but indeed the stark choice we face. And the lessons of UCS need to be studied and absorbed to help re-arm new generations of fighters, to make socialism the chosen future.