by Campbell Martin

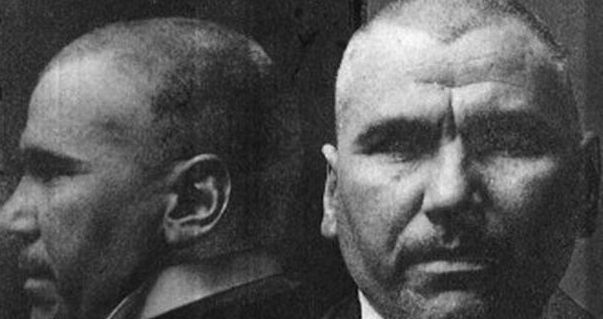

Throughout the years of the First World War and the ascent of Red Clydeside, one man stood out as a great socialist leader – John Maclean.

Maclean was born in Glasgow on 24 August 1879 to Highland parents and grew up in Pollokshaws as part of a poor, working class family. After completing his schooling he trained as a teacher and embarked on part-time study at Glasgow University, from where he graduated in 1904 with a Master of Arts degree.

In addition to his teaching at Lorne Street Primary School in Govan, John Maclean also took adult night classes where he taught economics to the working class, explaining the corrupt nature of the capitalist system and outlining a socialist perspective to organising society and economic activity.

Maclean’s staunch opposition to the imperialist warmongers in Britain and Germany ahead of the outbreak of hostilities in 1914 brought him to the attention of the authorities, and his continued outspoken criticism of a war that pitted worker against worker made him a marked man.

The extent of John Maclean’s socialist agitation and the strength of his opposition to the First World War were summed up by Willie Gallacher, one of the Clyde Workers Committee leaders, when he wrote in 1915:

“Maclean was everywhere. His indoor meetings were packed out, until he was forced to run two meetings a night. He was the centre of the anti-war movement; and all the other movements, whatever their tendencies, supported the general line he was taking.

He demanded an immediate armistice, with no annexations and no indemnities; along with this went his drive for the revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist class.”

On 6 February 1916, after speaking at a public meeting in Glasgow, John Maclean was seized by police. He was arrested as a ‘prisoner of war’ and locked-up in Edinburgh Castle, charged under the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA): trail was set for April.

The indictment against Maclean contained six counts of having made statements “likely to prejudice recruiting, to cause mutiny, sedition and disaffection amongst the civil population, and to impede the production, repair and transport of war material”. He pleaded not guilty to all charges.

The trail was held at the High Court in Edinburgh, where all 18 witnesses for the prosecution were serving police officers, with one Detective Chief Inspector confirming he had arrested Maclean on the orders of the British military. Twenty-eight civilian witnesses, including socialists James Maxton, Emmanuel Shinwell and Helen Crawford, testified for the defence.

The Lord Advocate prosecuting, during his summing-up to the jury, indicated his belief that it had been proved up to the hilt that Maclean had committed a felony punishable by penal servitude or even death, adding that, “Any man who at the present state of affairs interfered with the procuring of men for the army or with the production of munitions was a traitor to his country”.

After the defence counsel had spoken, the Judge told the jury the case was a difficult one, with a clear conflict of evidence provided by prosecution and defence witnesses, but added that “a verdict against the Crown would amount to a charge of conspiracy against the police”.

Despite the clear direction from the judge, the jury found Maclean guilty on just four of the six charges (not proven on the fifth and not guilty on the sixth). The judge sentenced John Maclean to three years penal servitude (imprisonment with hard labour).

However, unprecedented public opposition to the conviction and sentence led to massive protests and social unrest, which forced the authorities to release Maclean on 30 June 1917, having served 14 months and 22 days of the three-year term.

John Maclean was a strong supporter of the Bolsheviks in Russia, and their ultimate success in creating a workers republic following the 1917 revolution was seen by many Scottish socialists as the greatest inspiration to recreate the situation in Scotland.

But this provoked a further clampdown by the British authorities who introduced a ban on the publication of any ‘printed matter’ unless it had been passed by the government Press Bureau.

In early 1918, in recognition of his work through the Glasgow-based Russian Political Refugees Defence Committee, which had supported political prisoners held by the regime of the Tsar, the new Russian Government appointed John Maclean as the Bolshevik consul to Great Britain.

Maclean established the Consul of the Soviet Republic in premises at 12 South Portland Street in Glasgow, but the British government refused to recognise either the office or John Maclean’s position.

Then, on 15 April 1918, police raided the South Portland Street office and arrested Maclean. He was charged with sedition and trial was set for May. Bail was refused and John Maclean was locked-up in Glasgow’s Duke Street Prison.

Maclean conducted his own defence at the trial, which began with him refusing to plead (which was taken as a plea of not guilty) and, when asked if there were any of the jurors to whom he objected, the accused replied, “I object to all of them.”

There were 28 witnesses for the prosecution, including 15 policemen, eight special constables and two shorthand-writers employed by the police.

Maclean’s impassioned closing speech lasted 75 minutes and has become a cornerstone of Scottish socialist history. Opening his remarks, John Maclean said:

“I had a lecture, the principal heading of which was ‘Thou shalt not steal; thou shalt not kill’, and I pointed out that as a consequence of the robbery that goes on in all civilised countries today, our respective countries have had to keep armies, and that inevitably our armies must clash together.

“I had a lecture, the principal heading of which was ‘Thou shalt not steal; thou shalt not kill’, and I pointed out that as a consequence of the robbery that goes on in all civilised countries today, our respective countries have had to keep armies, and that inevitably our armies must clash together.

“On that and on other grounds, I consider capitalism the most infamous, bloody and evil system that mankind has ever witnessed.

“My language is regarded as extravagant language, but the events of the past four years have proved my contention.

“It has been said that they cannot fathom my motive. For the full period of my active life I have been a teacher of economics to the working classes, and my contention has always been that capitalism is rotten to its foundations, and must give place to a new society.

“I wish no harm to any human being, but I, as one man, am going to exercise my freedom of speech. No human being on the face of the earth, no government is going to take from me my right to speak, my right to protest against wrong, my right to do everything that is for the benefit of mankind.

“I am not here, then, as the accused; I am here as the accuser of capitalism dripping with blood from head to foot.”

Concluding, Maclean said: “I have taken up unconstitutional action at this time because of the abnormal circumstances and because precedent has been given by the British government.

“I am a socialist, and have been fighting and will fight for an absolute reconstruction of society for the benefit of all. I am proud of my conduct. I have squared my conduct with my intellect, and if everyone had done so this war would not have taken place. I act square and clean for my principles…

“No matter what your accusations against me may be, no matter what reservations you keep at the back of your head, my appeal is to the working class.

“I appeal exclusively to them because they and they only can bring about the time when the whole world will be in one brotherhood, on a sound economic foundation.

“That, and that alone, can be the means of bringing about a re-organisation of society. That can only be obtained when the people of the world get the world, and retain the world.”

The jury intimated it did not require time to consider its verdict: they found John Maclean guilty. The sentence, delivered by the Lord Justice General, was five years penal servitude.